'The MET' Tote Bag

New York City, 2019

Velvet Blue Saddle Bag

Worcester Park, 2021

Brown Button Clasp Handbag

Headingley, 2020

Through this essay, I will explore the process of reflection and the different ways this is achieved to experience a sufficient state of nostalgia. I will explore this through varied methods of documentation, crafting a catalogue of memorabilia. I want to explore the ways in which we can experience nostalgia and use these precious timestamps to form timelines of our lives. Reviewing my work, it seems evident I enjoy observation, objects and patterns, which I capture through exhaustive drawing. Using case studies and journals, I will explore the ways in which we digest our past, expanding this further by creating a body of work consisting of my findings through use of constraints, in order to direct my craft in a more refined manner. My research journey initially began as an exploration of locations I found myself in, for example my bedroom when I was ill or my kitchen, seeking out the ordinary and injecting joy through impulsive sketches and hundreds of pictures in my camera roll. Obsessed with the overlooked and mundane, I focused specifically on portraying fleeting moments in time that we forget in an instant, like light on my mirror or a fly landing on my window. Peony Gents ‘6 months in Kings Cross’ is a great example of digesting the space around you through immersion, documenting tiny everyday moments to create a snapshot of a specific place and time, with no conscious agenda. Gent accumulated a plethora of recordings from drawings, to found objects and chats with strangers. Said by Gent herself, ‘it is the layered connections, associations and memories that make a place’ (Gent, 2021) which I believe she applied to the discovery of new places. Am I searching for new and shiny places, or do places close to home hold even more for me? Gent’s statement pushed me towards the latter, considering not only my memories and associations with the familiar, but most importantly nostalgia. I began probing ‘the familiar’ and found myself looking at ‘home’. What was home and what made it feel that way? Being a third-year university student living 195 miles from London, the idea of home becomes a confusing state of mind.

Home to me is a safe space that I wake up and return to, a place in which I can reflect on the experiences in my day and relax. What makes up my home are the objects around me, the textures and patterns, and without them it would simply be an empty vessel. The objects in my house make up my home and thus my safe space, implying they hold a greater deal of importance than I formerly thought. I spend my days walking past them and pay no credit to the security they provide me with. This security branches off why I resonate with them so much, to which I would answer is because of the feelings of familiarity and nostalgia I feel when I think about them. When sat in bed, I am surrounded by a memorabilia timeline of my life. In ‘Nostalgia : A Psychological Resource’, behavioural scientist Clay Routledge argues that “contrary to popular opinion, nostalgia isn’t simply a retreat to the past. It would be more accurate to describe nostalgia as an effort to bring the past to the present”. (Routledge, 2015, p.32). The way for me to bring the past to the present in the rawest of forms, is through the physical act of drawing. I find myself truly reflecting and experiencing those feelings of nostalgia when drawing in the moment, scrutinising every aspect of the object in front of me, each detail unlocking a new memory. When the act of drawing is finished, those nostalgic feelings go and I am left with a final product, which looks almost hyper realistic, due to my obsessive documentation of every detail whilst being absorbed in the memory.

What does a drawing hold that a photograph doesn’t? The answer is authenticity, or as philosopher Benjamin Walter argues, ‘aura’. Walter explains in ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, that process reproduction in photography captures the aspects of images that escape natural vision, “bringing out those aspects of the original that are unattainable to the naked eye, yet accessible to the lens” (Benjamin, 1969). However, though this is the case it’s undeniable that the quality of its presence hence depreciates with the act. Walter states, “The authenticity of a thing is the essence of all that is transmissible from its beginning, ranging from its substantive duration to its testimony to the history which it has experienced”. He explains, “that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art...one might generalize by saying: the technique of reproduction detaches the reproduced object from the domain of tradition” (Benjamin, 1969). A photograph can capture a moment on the go, whereas a drawing allows you to absorb every morsel of that moment - the longer the process, the more time to reflect. I do question whether it is drawing itself, or if drawing is the passive act of looking intently and observing for a long time, that allows myself to relive that memory. Whilst drawing, I reflect on how I acquired the object - where did I buy it? Was it given to me? Whose is it? Smaller questions like these veer me away from focusing too much on the drawing process; I don’t overthink my mark-marking or the steps I should be taking to create my image. Observational drawing becomes a state of meditation?....or perhaps escapism is a better word. Writer Mark O’Connell explains that the piece “has a powerfully cumulative effect that requires compression in time in order to be fully felt”, to which I infer that the book is to be ‘experienced’, rather than read – “it benefits from a mounting sense of absurdity that would be lost if you were to just pick it up intermittently” (O’Connell, 2011). Springboarding off this thinking, it is at this point that I would say drawing isn’t a passive act of observation, as I myself have chosen to use this constraint as a means to delve further into the reflection process.

How does the object make me feel? Do it’s stains, blemishes or cracks evoke memories that add chapters to its lifetime? These physical appearance interrogations aid my obsessive drawing nature - the more character, the deeper the core memory. An example of this way of working can be seen through the works of artist Gregory Blackstock. Blackstock thoroughly explores his subjects of interest by producing meticulously detailed drawings to create typologies, “classifying them in works that reflect a deep knowledge” (Artsy.net, 2020). His highly detailed drawings catalogue an array of visuals, from dog breeds to historic fortresses, with the aim of creating “order out of the chaos that is the vastness of the world”. I resonate with this point myself, as I prefer to focus on individual objects around me rather than the room as a whole, almost to break down all my memories into smaller chunks and provide a sense of structure. Is this because my memorabilia becomes part of the room decor instead? Are there too many memories to each object that I have to focus on them one at a time? Courtesy Garde Rail Gallery states “it has become evident that nearly all of the objects Gregory chooses to put on paper have a profound personal affect for him; mostly stemming from childhood memory and what that world looked and even sounded like” (Outsiderartfair.com, 2013). His practice adopts an obsessive approach through this cataloguing process, illuminating his nostalgic reflections for people to see all at once. By adopting this same level of detail in my drawings, I could look simply at the object or my final recordings in order to reminisce, however I cannot truly do so until I am physically drawing it.

Using this introduction into cataloguing, together with Craig-Martin’s reference’s to display and showcasing, I was led to question how this applies to me and how I digest nostalgia. I find that when I am home after being away at university, I’m returning to the timeline of my life, arranged around me like timestamps on the walls, floors, corners and crevices of my house. These objects; cushions, mugs, vases or fluffy slippers when regarded as a collective, could almost act as camouflage. As mentioned before, they lose their sense of identity as a core memory in my mind, and become ‘part of the furniture’. It is not only until I focus on an individual object and visually record it, that I am able to comprehend it in its fullest form. Viewing these objects from an ethnographic point of view helped me realise that regardless of location, being home in London or in Leeds, it’s the physical object itself that grounds you to a memory. If I brought a plain white bowl from home to university, when preparing dinner, I’m still reminded of home and leaving this bowl unwashed on the side of the sink, consequently facing an angry mother. Similarly, if I return home from university and notice a new addition, my memory of this is formed there and then. This suggests that inclusion of the environment or location is not only irrelevant but if anything, clouds the original memory. Although the environment is changing, the object stays the same, demonstrating that the object holds more significance than the place. I am desperate to celebrate this idea through my practice, by providing these objects, call it ‘memory snippets’ that encompass my nostalgic reflections, with their own limelight. I want to place them in their own box, to allow them to be acknowledged and valued.

Chicken Ramen Soup

Nottinghill, 2017

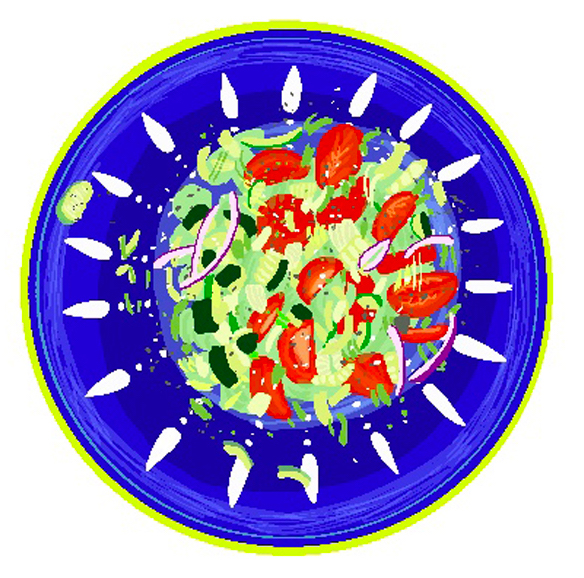

Vegetable Salad

Hyde Park, 2019

Roast Dinner

Leeds, 2020

Supernoodle Ramen With Egg

Addiscombe, 2015

Mexican Open Burrito

Kingly Court, 2021

Camembert and French Stick

Hyde Park, 2019

Avocado on Salmon Fried Rice

Shirley, 2018

Fried Rice Medley

Hyde Park, 2021

Truffle And Duck Fried Rice

Chelsea, 2021

Prawn Gyozas

Chelsea, 2021

'Ollie' the Ctenanthe Setosa

Dobbies Woodcote Green, 2021

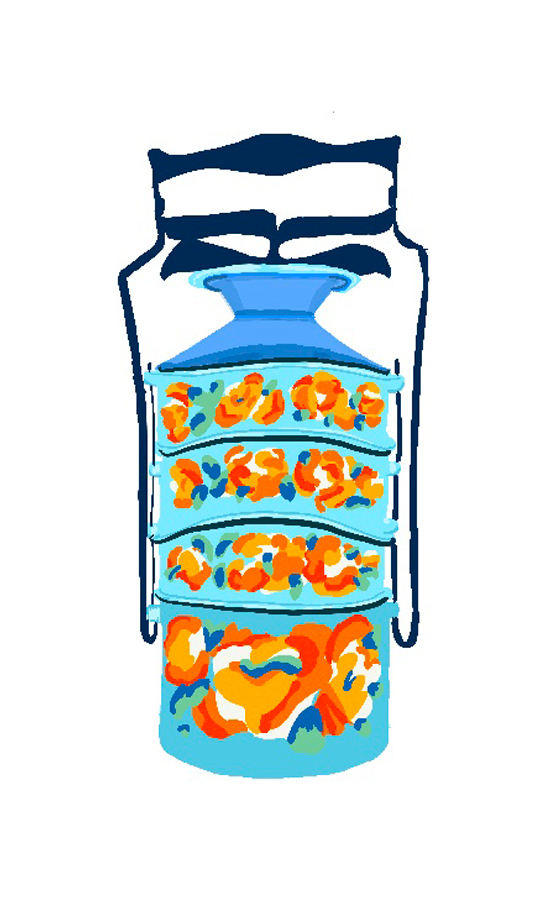

Malaysian Tiffin Box

Kuala Lumpur, 2005

Bamboo Sticks In Ancient Greek Olive Oil Urn

Kuala Lumpur, 2007

Cheam Village, 1996

Antique Genever Gin Bottle

Esher Bootsale, circa 2001

Cow Cushion

IKEA Purley, 2010

Fluffy 'Home' Slippers

Primark Sutton, 2021

Papaya Tree

Seremban, 2018

Ceramic Decorative Ball

unknown, 2014

White Bowl With Bolognese Stains

Addiscombe, 2021

Moroccan Light

Next Home, 2014

Purple Glitter Bauble

Monsoon London Victoria, 2019

Buddha Decorative Cushion

Achicha, 2013

Bowl Of Homemade Cacio e Pepe

Addiscombe, 2021

Jack Wills Mug

Jack Wills Brighton, 2016

Giant Floor Cushions

gifted, 2013

Audrey Hepburn Coffee Table Book

Tiffany & Co NYC, 2019

Hand Of Fatima Wall Hanging

Marrakech Souk, 2017

White Sequinned Bauble

Monsoon London Victoria, 2019

Table Christmas Tree

M&S, 2020

Box Of Macarons

Costco, 2021

Peacock Bauble

Covent Garden, 2018

Amber Glass Bauble

Kuala Lumpur, 2008

Blue Window Box

Wyevale Shirley, 2015

Hanging Light With Hanging 'Initial' Baubles

unknown, 2000

Museum and display table layouts are an interesting concept to consider- not only is the object left centre stage, but also accompanied quite literally with a timestamp and description for others to learn about and possibly relate to? Author and chief curator of the National Museum of World Cultures, Henrietta Lidchi (1997:159) explains the role of representation in museums, stating that “museums reflect a larger order of phenomena in microcosm” (Emmison & Smith, 2000, pg. 121). These objects are a door to an abundance of memories and experiences, sparked by methods of observation and drawing, in which others can too, upon viewing, walk down memory lane in ways of their own. I’m drawn to the ‘classification’ aspect of museums too and wonder if this draws links to my obsession with categorising and cataloguing objects too.

Relating back to Michael Craig-Martin, I question in what way objects in a museum should be viewed as important? If ancient civilisations could choose what objects they leave to encapsulate their culture for future generations to see, would the museums of today look the same? I would say initally, we choose to curate objects we feel are important to us at the time, perhaps due to usefulness or aesthetic attraction as it follows a trend. However, I would argue we can’t predict what objects hold the most meaning until they have produced enough meaningful memories lasting longer than the present. Relating to my current practice, I chose to document my vast necklace collection as one of my ‘categories’. As I wear these necklaces all the time currently and they follow today’s fashion trends, you could say this was an immediate aesthetic attraction. Although my necklaces are important to me now, will they be objects that evoke a lifetime of memories in the future? Comparing these to the plain white bowls from childhood, or meal favourites throughout my life, although not necessarily aesthetically appealing, my memories of these objects have snowballed overtime, allowing me to have made deeper associations with them.

Cacio e Pepe

New York, 2019

Iced Tea In A Can

New York, 2019

Plate Of Toast Smothered In Apricot Jam

Addiscombe, 2022

Today’s society will find objects from ancient times intriguing, viewing them as ‘important’ regardless of what they are because much time has passed since they were used daily. Lifestyles today are worlds apart hence no matter the objects that survive, future generations will still captivated - for example, a Victorian chimney sweep’s shoe holds years of the owner’s memories through wear and tear to ‘Gen-Z’, but it’s likely the owner of the shoe thought nothing of it at the time.

On account of this, I found it difficult to make detailed drawings of my necklaces. I lost interest to the point where the drawing process overtook the reflection process - the opposite to when I drew my bags. Perhaps this was because visually, there was less to deconstruct, hence less detail to examine. Fundamentally, the structure of each necklace is the same and so they became boring to draw. This made me question if I would have a different experience drawing these necklaces in a couple years time, by then they may have grown in meaning and I would maybe have more to reflect on? Using Routledge’s theory of bringing the past to the present through my detailed drawing methods failed with my necklaces, however I found that photographing them, captured them in their true and correct form. Linking my earlier point, photographs are an immediate way of capturing a memory at a glance, which applies better to objects I have only owned for a short period of time; i.e don't hold as much nostalgia. Photographs promote the aesthetic appeal that draws that person to the object in the first place. I combined both processes when I drew from previously captured images on my phone. This was interesting to reflect on as although it isn’t necessarily drawing from life, a picture was the most suitable format for me to preserve that memory on the go, at that time. Artist, Joy Miessi, turns her personal experiences into visual memorabilia by using found photographs to make drawings. She states “it sparks memories when looking through albums” (Miessi, 2020, p.45), suggesting that a photograph simply wasn’t enough and that drawing elevates the nostalgia when paired together. Although photographing may have been appropriate in the case of my necklaces, I still chose to display the original drawings, the number of drawings perhaps acting as a measure of how deep the memory resonated with me before I chose to stop?

'Earthy' Chunky Bead Necklace

Brighton, 2021

Clear Bead Silver Necklace

West Wickham, 2019

Simple Gold Chain

Wimbledon, 2020

Pastel Bead Necklace

Wimbledon, 2020

Deep Red Mini Bead Choker

Worcester Park, 2021

White bead Necklace

Headingley, 2020

Aqua Fine Bead Necklace

Clapham, 2021